By Theo Gough

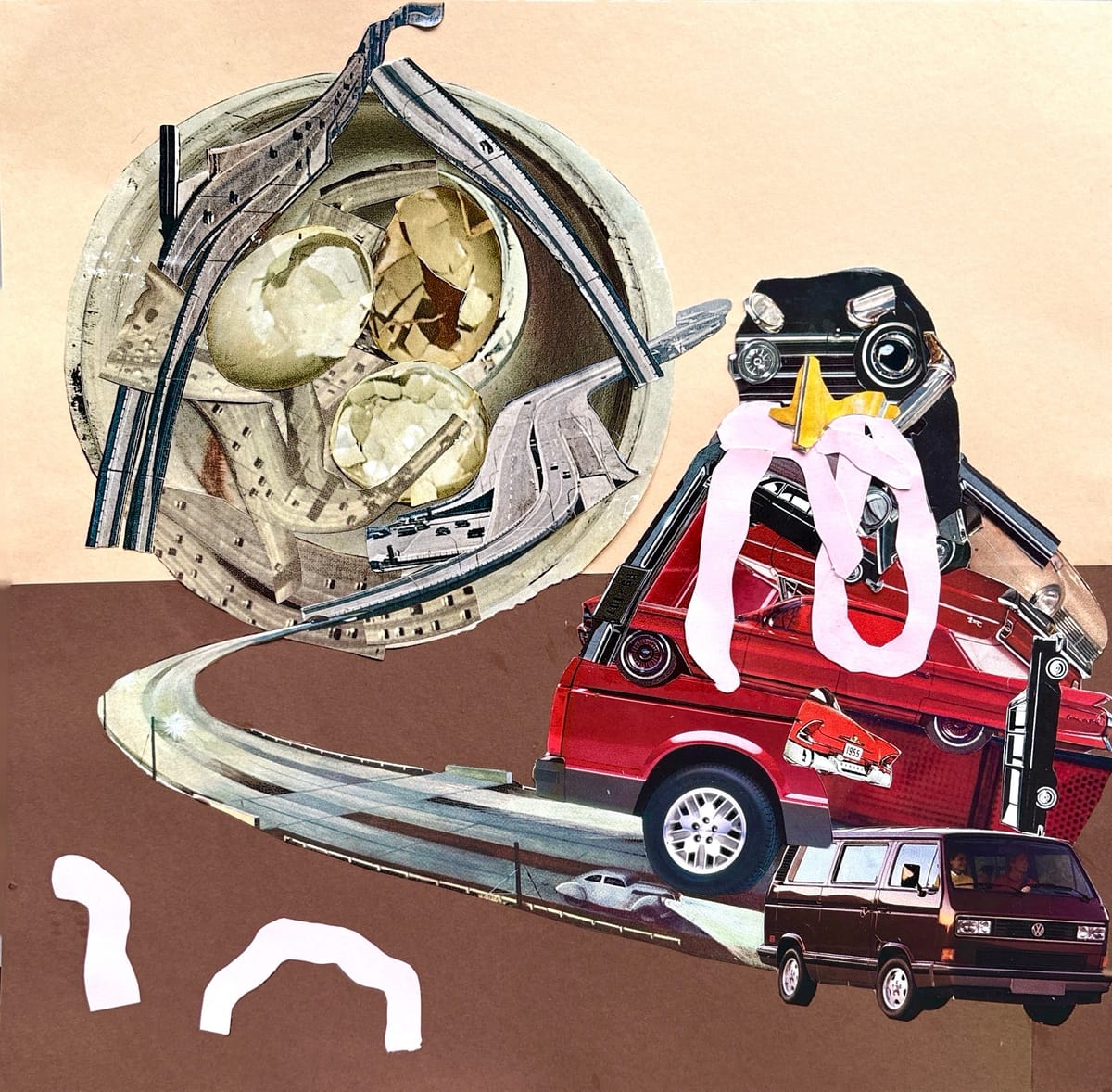

Artwork by Nakeshia Diop

On a clear and sunny summer day in London, a group gradually amassed outside the National Theatre, on the bank of the river Thames. At 7.30pm we set off with no set route, destination, or end time. As we made our way through the city, you’d hear us first: hundreds of bike bells ringing all around, huge bike-mounted speakers blasting music, and a few locked Lime bikes clicking along. Then you’d see the eclectic group we were: riders covered in glitter, head-to-toe black, or anything in between; on wheelchairs, scooters, tandems, penny-farthings, Bromptons, and custom-made bicycles with the rider six feet in the air. This is the scene at Critical Mass.

Critical Mass is a global tradition that takes place in over 300 cities on the last Friday of every month. Started in 1992 by a small group of San Francisco cyclists to assert their rights to the street, the basic premise has remained the same ever since; without any official permission, riders gather at a set point and time for a group bike ride. The route is decided spontaneously. To make sure everyone stays together, a few riders will block traffic at an intersection (regardless of traffic light colours) to allow the group to ride in one large, unmistakable ‘critical mass.’

From 50 riders in the initial San Francisco group, it grew to a few thousand riders in the city within a couple of years, then spread worldwide. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when, where, and how far it now reaches because Critical Mass is not an organised movement. It is a decentralised, organic gathering with no hierarchical leadership structure. Riders decide collectively, spontaneously the route for the ride and are free to join or leave the group at any time.

The reasons for joining are varied. Some people attend because of environmental concerns, some to promote safe cycling infrastructure, and others just for community and fun. It’s a true melting pot. Underpinning them all, though, is a desire to invert the standard isolation and hierarchy of city life with something joyful, communal, and free.

Increasingly, the design of cities and urban space is driven by the interests of capital rather than the needs of people. Wide roads and endless car parks swallow up space that could be used for affordable housing, green space, or gathering. Public squares are flattened into shopping districts where hanging around without buying is discouraged and even criminalised. It’s an urban landscape that confines, surveils, and commodifies us.

Car-centred design is one of the clearest examples of planning that isolates. Zoning laws often segregate commercial and residential areas to drive up property values, forcing people to travel greater distances between home, work, and essential services. As public transport budgets shrink (or barely existed to begin with), owning a car becomes a necessity. This structural dependency is reinforced symbolically: in adverts, cars are positioned as symbols of freedom, status, and success. People are pushed to buy newer, bigger, fancier models—often on finance. The outcome is a vicious, self-perpetuating cycle: people have to (and want to) own a car, and because they do, city planning focuses itself on building even more car-centric infrastructure.

Car-dependency is impoverishing for everyone, financially and socially. Between the car itself, maintenance, fuel, and parking fees, owning a car is expensive. One recent report found that the UK’s poorest households spend a staggering 25% of their income on car ownership. Everyone else on the road is treated as secondary: bus passengers are forced to sit in traffic on clogged roads; cyclists are pushed to the edges of the street in ways that jeopardize their safety; pedestrians are made to wait for permission to cross, provided there’s even a sidewalk to walk on. And, of course, for the planet, the impacts of car-dependency are catastrophic.

Critical Mass continues, over thirty years on, because it offers a glimpse of another way. For a few hours each month, cars become secondary. The ride holds a mirror up to the system, making people notice the unsafe roads, unfair distribution of space, and lack of human connection that are the default norm. It’s a reminder that our cities could be designed to reflect our needs and our joy.

This inversion of the status quo is striking—on safety, particularly. On this ride, we stopped in Shadwell to install what’s called a ghost bike—a white-painted memorial bike—in honor of Matheus Piovesan, who was tragically killed in a hit-and-run as he cycled home from work. Blocking traffic in that same spot for nearly twenty minutes, we were visible in a way that Matheus was not. Feeling the safety-in-numbers at Critical Mass was a stark and sobering contrast.

The route itself was another sort of rebellion. We rode down the middle of Tower Bridge, into a lane designated for oncoming traffic, down the fast lane of a dual carriageway. These are all normally prohibited areas for bikes, instead optimised for high-speed car commutes. A few rides ago, Critical Mass London made news for venturing into the Silvertown Tunnel, a new £2.2 billion project where cyclists are banned and need to wait for a shuttle bus to take them through. Riding through it together made the restriction seem absurd—and helped build consensus that these design choices that prioritize cars over everything else shouldn’t be repeated.

Another obvious departure from the status quo is the speed at which we moved through the city. With cars on the road, cyclists feel obligated to pick up the pace or get out of the way. When Critical Mass took over the streets, the slowed speed felt powerful. We could stop, look around, or pause on the side of the road with a drink. Space that is normally travelled through without a thought became space to be enjoyed.

That slower pace fostered conversation and interaction in a way driving never could. People joked, sang, danced, wheely-ied, and generally enjoyed themselves. One bike even had a grill fixed to the back with a few burgers cooking as we went along. Far from the isolation of a car, Critical Mass enabled real connection and a clear sense of togetherness.

That feeling of community was strongest at the end of the ride. Sam The Wheels (also known as Clovis Salmon) was a beloved Brixton figure who ran a bicycle repair programme from his home—famous for the massive piles of bikes outside. He sadly died earlier this summer, and his funeral fell on the day of Critical Mass. We rode to his house, where the wake was still underway, and his family and friends lined the road as we stepped off our bikes for the first time that evening. It was a special moment.

So what does Critical Mass achieve every month? It’s an important reminder that alternative cities and alternative worlds are possible—that just because things are the way they are, that doesn’t mean you’re alone in wanting them changed or that such change is impossible.

As precedent, there have already been many hard-won victories; in Amsterdam, streets once packed with cars have been so fully transformed that bike congestion is now becoming the issue. In London, The Economist recently reported that more people cycle each day than drive. Cycling gets plenty of praise, and for good reason: it’s healthier, greener, more space-efficient, and fun.

Still, it is not immune to co-option. Increasingly, cycling has become associated with (and catered to) affluent, white, largely male riders. The image of cycling—expensive road bikes, branded gear, and Strava leaderboards—often reproduces the same capitalist values of speed, competition, and consumption. Biking is absolutely something more people should do, but it is not, in itself, a radical act.

That’s why Critical Mass matters. Cycling can be co-opted, but reclaiming the streets, slowing them down, and making them feel safe for everyone in a collective, people-powered movement cannot be. If you want to feel how different a city can be—open, communal, joyful—join a Critical Mass near you!

How to join a ride:

You can find your nearest Critical Mass online. Enter with an open mind and remember to have fun. Feel proud that you are reclaiming your right to the city and, in a small way, reshaping urban space to meet the needs of people first.

If you don’t have one in your city or are not yet a confident cyclist, then there’s bound to be a similar cycle group. They are always welcoming and help ensure safety in numbers. Find a group ride that makes you feel welcome. Some focus on marginalised groups: check out Banditz (Johannesburg), Broad Bikez (London), DC Queer Bikes, and Good Co. Bike Club (NYC). Some even do night rides to build familiarity and comfort at times with fewer cars.

Help us keep Radish free to access. Consider becoming a member or giving once.