Belgian documentarian Johan Grimonprez’s 2024 “Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat” overflows with energy, like a full glass brimming over, shaken by the vibration of thunderous music, rapturous applause, or turbulent protest.

“Soundtrack” highlights the United States Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) efforts to exert soft power throughout the Cold War via a massive campaign of cultural export. In the decades-long attempt of the U.S. and allied global capitalist interests to undermine socialist movements throughout the world, the U.S. conducted a propaganda campaign presenting capitalism as the bastion of freedom and creativity.

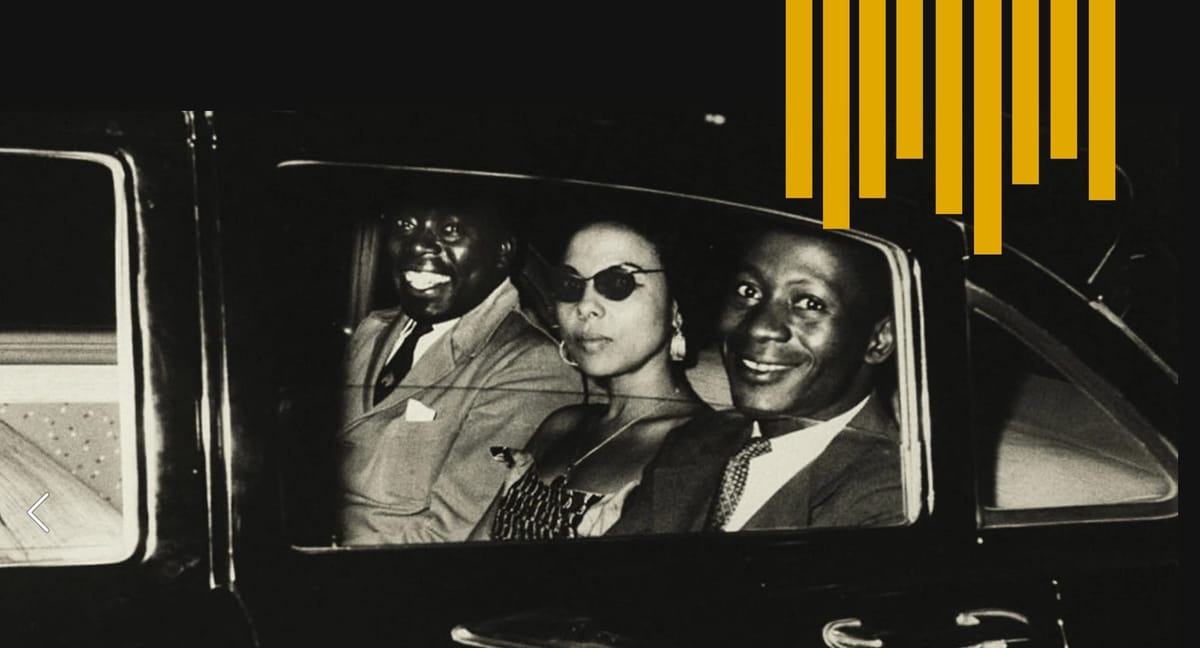

This campaign involved the CIA funding of abstract art movements through ties to the New York Museum of Modern Art and individual artists like Jackson Pollock. It also relied heavily on the art of Black Americans, particularly through jazz. Jazz greats like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Dizzy Gillespie were sent by the State Department to perform in Cold War-contested nations, the Congo among them, for “jazz diplomacy.” The depth of the CIA’s involvement was often obfuscated to the artists, many of whom publicly opposed the US’s political intervention abroad.

The documentary has no narrator and no interviews. It relies almost entirely on archival footage from the explosive year of 1960—the year of the assassination of Congolese independence leader and prime minister Patrice Lumumba after serving only 10 weeks in office. However, the film manages to produce a cohesive narrative with jazz in the driver’s seat. The music is what ties the documentary’s many elements together, acting sometimes as glue, other times as disruption in the documentary’s trajectory.

Archival footage is spliced with flashes of excerpts from history books and direct quotes from political actors, complete with academic-style citations.

In fact, one of the documentary’s most impressive feats is precisely its ability to keep itself together while so many of its elements feel as though they are spinning outward. The music mimics this movement, with a powerful rendition of “The Ballad of Hollis Brown” performed by Nina Simone. Simone repeats piano chords alongside the intense build of a drumbeat, chugging like a train, her voice cutting and full of intensity. The song itself offers a scaffold for the pacing of the documentary, for the audience’s sense that something disastrous is happening and no one is there to stop it—we’re just along for the ride.

The documentary also underscores the crisis of domestic racism and segregation in the U.S., which threatened to undermine the country’s soft power. The Soviet Union regularly pointed to Jim Crow as an example of the deep inequalities experienced in the United States. And as more and more liberated African nations joined the United Nations, the absurdity of the idea that the U.S. could have any global interest in the wellbeing of those they would otherwise oppress within U.S. borders became apparent.

The documentary moves with all the chaos of the 1960s, largely confined within the single year that kicked it off.

Splashed throughout the film are figures like Fidel Castro and Malcolm X, including Castro’s debut at the United Nations in 1960 (and his removal, followed by an invitation by X to Harlem). Far from digressions, the incorporation of such threads—Black liberation and nationalist movements in Harlem, socialist revolutions that upturned societies of exploitation—contextualize the plot to assassinate Lumumba in precisely where it stood: a global shakeup of the world order.

The film highlights the Bandung Conference of 1955, where 29 African and Asian countries met in Indonesia in what would become a founding moment for the Third-World Movement: the struggle for national independence of colonized or formerly colonized nations, and against global colonialism and imperialism. In the years after Bandung, these nations formed a powerful voting bloc in the United Nations, empowered not by GDP or military strength but by the sheer number of countries represented.

Their anti-imperialist influence was threatening—and "Soundtrack" pulls back the curtain on the CIA’s collusion with private capital, war-mongering interests in mineral mining (uranium then, cobalt and lithium now), and the Belgian government to crush Congolese self-determination. British corporations sought mining profits in Katanga, the U.S. aimed to stamp out socialism worldwide, and Belgium clung to its colonial spoils.

Scenes of Nazi mercenaries brought to Katanga, the wealthy white state in the south of the Congo, makes the stomach turn. Interview footage of British M16 and US CIA operatives who plainly and flatly recite their orders to assassinate Lumumba, turn the blood cold. Images of Congolese liberation leaders viewing their own ancestors’ stolen belongings from behind glass, housed at the Belgian Royal Museum for Central Africa, shatter the heart.

“Soundtrack” also attempts, although somewhat haphazardly, to connect the assassination of Lumumba and the imperialist powers’ collaboration to undermine Congolese independence with contemporary conflict that has riddled the Congo for the last several decades. Though the connection was important, the references to modern day were the most discordant aspects of the film. However, the point is driven home clearly: not only are the same forces to blame for the suffering and destabilization in the Congo today, but the forces that destabilized the Congo in 1960 never left.

“Soundtrack” is among the most innovative and unique documentaries I’ve ever seen, and should be required viewing for anyone interested in the history of anti-imperialism, American jazz, and the strange thread that ties them together.